Without accuracy an answer is meaningless, but when designing research are you really focused on how accurate the answers could possibly be? Here are four key factors to consider in order to ensure insights are based on a solid foundation of accurate answers.

-

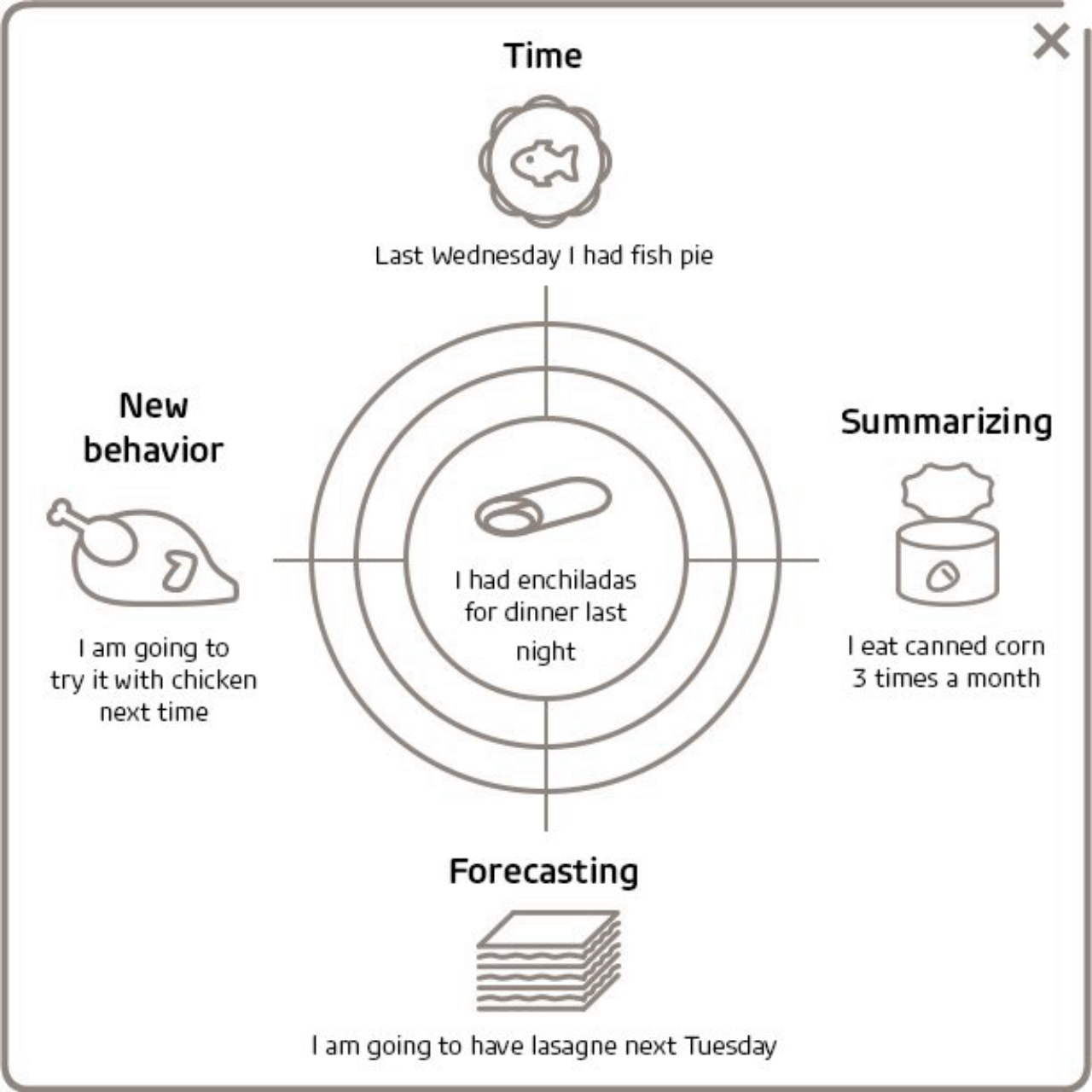

Predictive versus behavioral

It is universally accepted (if occasionally downplayed) that behavioral questions illicit more accurate answers than predictions.

I know the answer to the first because I looked at the clock when I fired up my laptop but my second answer has a higher margin of error; I may finish a minute or two late or bump into a colleague on my way to the lift. The answers to predictive questions are based on a simplification of the world that ignores many of the complexities and unknowns.

-

Established behaviors

We are creatures of habit and our lives are made up of hundreds of repeated actions. The more established or routine behavior is, the more accurately we can answer questions about it.

To buy bananas, I go online to order my groceries – something my family and I do every week (usually a Monday). Bananas are in my favorites section and have never been out of stock.

By contrast, the best value chewing gum is at the pound shop, somewhere I rarely go although my wife will go into town at least once a week. This only requires me to ask her, but the cue reminding me I have run out typically comes when I am trying to avoid biscuits at work.

Despite my desire for both products being the same, my answer about bananas is more accurate because the infrastructure is already built into my life, the occasion, the cue and the availability of the product.

-

The question of time

A third major stumbling block for answer accuracy is time.

I can tell you I had vegetable enchiladas for dinner last night and I can tell you why (I didn’t get home in time to make the lamb tagine; someone accosted me by the lift). But in a week I will have entirely forgotten my lift-based delay and will probably only just about remember the enchiladas. We forget and confuse things over time, particularly behaviors with little emotional attachment. When did I have the fish pie last week – Tuesday or Wednesday night?

Larger decisions will stick in the mind for longer, like buying a car, but the rate at which we post-rationalize remains the same. We may remember the day we purchased our last car but could we remember how much sleep we had the night before, or that the toaster was on the fritz that week? Such happenings may have influenced our purchase decision of the extended warranty, but when asked six months later we will give generic reasons. Because when we can’t exactly remember we assume it must have been for a logical reason.

-

Summarizing our behavior

As humans we are wildly inaccurate when it comes to summarizing behavior because our summaries or averages are often based more on how we like to think of ourselves as opposed to how we actually behave.

Because I feel guilty every time I use a device to stop my son wriggling away at the table, I would offer a lower than average statistic. My brain focuses on the successful times where we were TV free.

By contrast, I like to think of myself as a runner; on Wednesday I run with a friend (c.10 miles) and aim for another run at the weekend (c.5 miles), so I summarize this as probably 10-12 miles. My GPS running app – unencumbered by my aspirations – puts my average at 7. My brain down plays all the times we cancelled our run or the weekends I went away.

Combining points three and four only multiplies the effect; that is, summarizing behavior over long time periods significantly reduces accuracy.

Finally

All of this is not an expression of the futility of asking questions often they are unavoidable, but we need to consider what we are asking respondents to do. Ask ourselves “how hard is it to be certain of the answer to this question?”, can we ask something that will be more accurate? Fundamentally, inaccurate answers undermine the quality and strength of the insight that they generate.

For more information, please contact Sam Carter at samuel.carter@gfk.com.