This is the third blog in our series about changes in urban mobility due to altered consumer behavior during the COVID-19 crisis. Read about how urban mobility has changed and what will last after lockdown and 4 futures for urban mobility post-lockdown.

Last week, we laid out four possible scenarios for how people’s city mobility behavior will continue after lockdown is lifted. In this article, we look at what city planners can do to grasp the one-off opportunities within each scenario in order to influence ongoing urban travel behavior. As before, these are based on actual behavior trends, combining MOTIONTAG mobility behavior, GfK consumer behavior data, and views from leading experts in the field.

What to consider in a future with no real change in urban mobility

It is a sobering truth that the current pandemic is unlikely to be the last one we experience – so cities need to learn from the present crisis. Mobility experts are pointing to two key aspects that must be considered for all mobility modes and lifestyles:

- Infrastructure changes

- Develop shorter ways to gain access to essential needs (daily shopping, education, workplaces), plus smart logistics hubs in cities to support increased online shopping.

- Expand existing infrastructure and make room for active modes of mobility, including micro-mobility services.

- Use of existing technologies

- Improve the responsiveness and resilience of cities, for example via intelligent transport systems guiding traffic based on changing demand for different modes. With limited space to accommodate all modes of transportation, the need for an efficient, adaptable and intelligent transportation system is increasing.

Part of this scenario is that people are trying to avoid public transport in the short term. But it would be a mistake to cut investment. Public transport will remain the backbone of long-term urban mobility. Instead, we need to rethink how cities transport people and encourage on-demand and ‘shared individual’ mobility services that complement the existing infrastructure and services. This could well be the time to accelerate the adoption of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) as a necessity in delivering more efficient and safer public mobility.

Alongside this, measures will be needed to encourage people to restart their use of public transport early on. Several solutions have already been implemented, such as more frequent deep cleaning of interiors and mandatory wearing of masks by passengers.

A major development of the current crisis is that both startups and public transport companies are now sharing data on their passenger levels throughout the day – for inclusion in trip planning apps. This better understanding of passenger flows, married with real-time guidance of people during transit, is the foundation on which urban travel planners can deliver much more comfortable and efficient ways of transporting people across cities.

What experts say:

The most important aspect for city planners is resiliency planning. This is too often seen as a fancy hypothetical event and ignored by professionals in the traditional realm. But learning from COVID-19 travel data is giving us new understanding of what happens when a percentage of demand for wider mobility or luxury consumption disappears. Many large infrastructures, such as highways, airports or expensive parking facilities, will face difficulties in justifying funding when they have a lower chance of remaining used.

– Dewan Karim, Integrated Mobility and Safety Specialist, Dillon Consulting, Canada

How to foster a future with a full ecosystem of urban mobility modes

To make the “full ecosystem” future a reality, we need to look at urban mobility as a connected ecosystem and integral part of our society. We must consider the knock-on effects of subsidizing certain modes of transport over others and foster the changed mobility trends that the crisis has forced on us, to encourage sustainable environmental aspects.

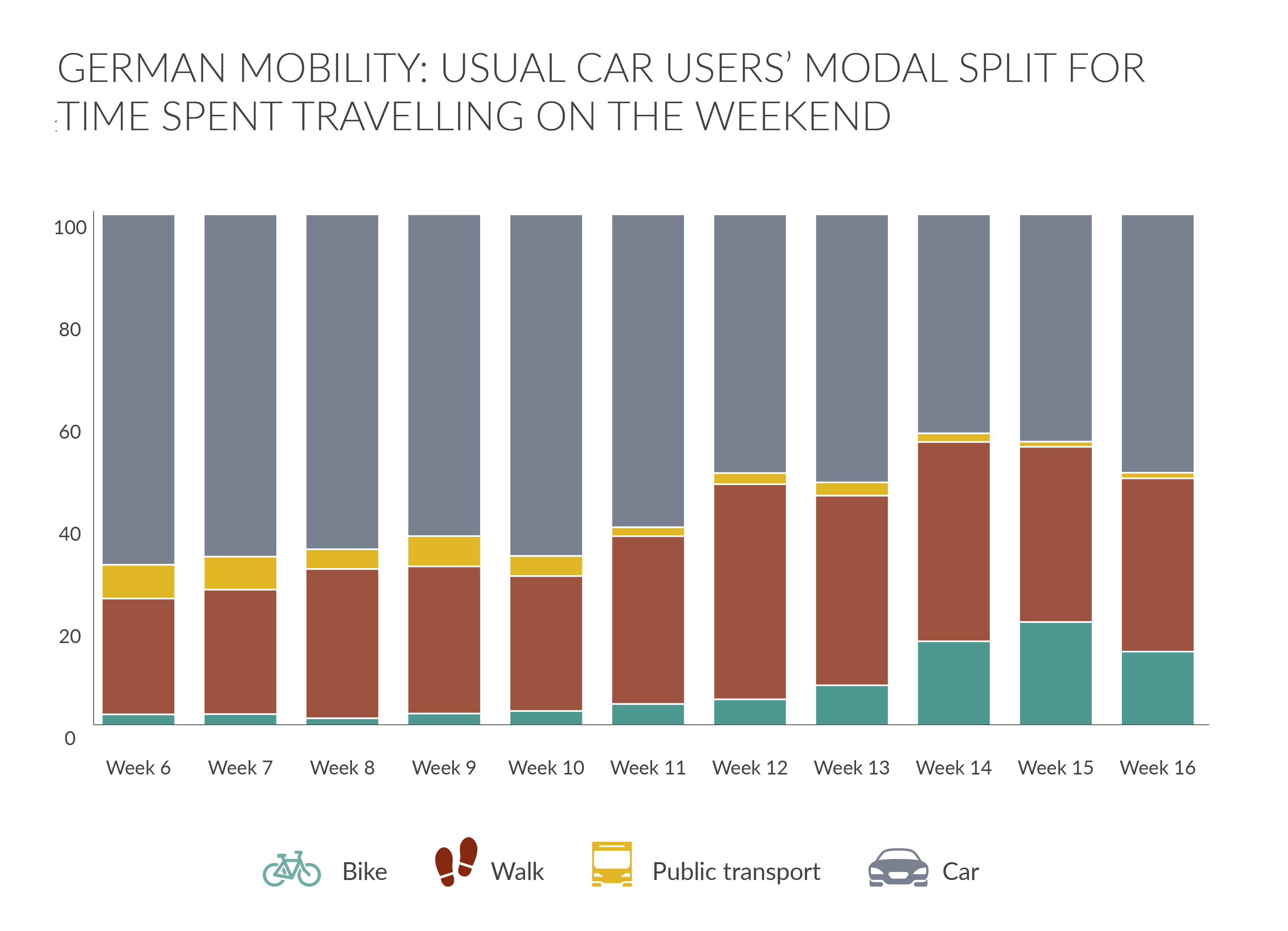

Source: MOTIONTAG. Weekly comparison of the share of time spent traveling by regular car drivers on weekends.

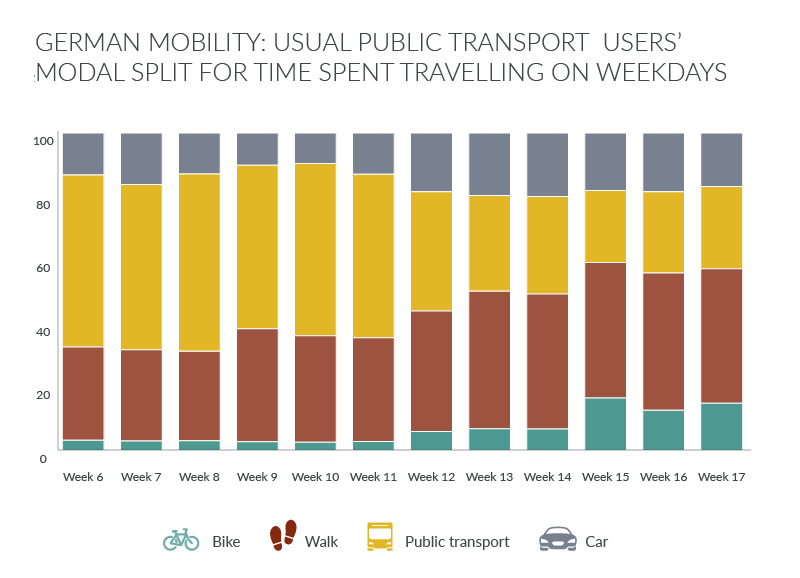

People are already spending more time on active mobility—and that counts for regular cars users as well as public transport. But, at the same time, car use on weekends has started to increase again, while usual public transport users on weekdays still mainly rely on walking or biking.

City transport planners need to delve into people’s purposes for trips, and the mobility demand related to these, in order to provide attractive alternatives. These could include subsidizing modes of transportation with a high return-on-investment from a societal point of view – such as electronic bike hire services or switching vehicle fleets to electric models.

Source: MOTIONTAG. Weekly comparison of the share of time spent traveling by regular public transport users on weekdays.

Incentivize off-peak travel

Historically, rush-hour travel has been a big challenge for public transport operators and urban authorities. Encouraging people to switch to non-peak patterns will be important in any future that looks for a “full ecosystem.” Financial incentives would only help to an extent.

The current crisis and enforced changes to our lifestyles opens a partial solution to this problem. Old assumptions about the inevitable and continuous increase of peak-time travel can be reassessed, with many businesses already talking about at least partially continuing a work-from-home approach and perhaps staggered work shifts. By encouraging these measures, city planners can relieve congestion on roads and public transport.

What experts say:

Now is the time to ensure the recent growth in cycling continues, by providing cycling infrastructure (temporary + long term) and subsidies to help people buy a bike, including electric ones. We know from facts that the return on investment for cycling is huge, but despite this, authorities have done relatively little, so far, to foster it. Now really is the time to do so. Added to that are incentives to use public transport during off peak times. Incentives don’t have to be only financial, let’s be inventive! Why not gamification around sustainable behaviors?

– Melina Christina, MaaS Product Manager, RATP Dev, France

Urban mobility considerations to support a rise in country living

To facilitate this type of future, city planners must investigate commuter flows and really understand the people behind the demand: their mobility preferences and what is driving the need for their trip.

If people take advantage of today’s wider acceptance for remote working to reassess where they can live—and potentially move out of dense city centers— their mobility needs will change. The immediate effect will be on traditional peak hours. These will have to be re-assessed to determine whether they are still valid, on which days, and whether we have a new pattern of numerous smaller peaks. Alongside this, the catchment area of a city center commuting could be subject to change.

Urban mobility planners need to track the new norms: which weekdays, and time of each day, are people commuting? And from where to where? These evolving and changing commuting patterns will need monitoring on an ongoing basis, as the new norms emerge and solidify.

The key questions for urban planners will be:

- Volume: How many people need a mobility service at a given point in time?

- Origin-destination matrices: From where and to where in the city do the commuters have to go?

- Characteristics of neighborhoods: How are these structured today, and how are they changing?

- Alternatives: What is the best option to cover the distance right now – from the point of view of the consumer, and the point of view of the environment? What is the go-to state, and the target vision?

These questions can be best answered via data: daily mobility tracking, metrics on consumer purchasing power, consumer attitudes towards, and perception of, alternative mobility solutions, to name just a few.

For example: for people who move out of city centers, their trips ‘downtown’ will have a different purpose. Instead of just commuting, these will be about social or leisure trips – in which case, factors like the convenience and flexibility of transport might start to trump price on these occasions. The task, then, for travel providers will be to create offers for demand-responsive, convenient transport options to and from the outskirts of a city and suburbs. This is the perfect playground for public-private partnerships where e.g. ride-pooling services complement public transit or substitute lines with questionable unit economics.

How to support the preference for local proximity after lockdown

During lockdown, we probably all explored our local neighborhood more than ever before; partly because we had time to do so, another part because we were discouraged from leaving far from our homes. Added to this, our local loyalty has increased, as people suddenly realize the value of threatened local businesses, and even help in crowdfunding neighborhood shops and restaurants.

This new appreciation and protectiveness for ‘local’ will live on, even after lockdown. To foster this ‘local-first’ behavior for a future that avoids unnecessary travel, city planners can take active steps that support multi-functional, decentralized urban centers. Opposing this buy-local behavior will almost certainly lead to consumer disengagement.

First, the neighborhood citizens need to be involved in the planning process, to specify what needs they are looking to be fulfilled in their closest proximity: what is an absolute must, what are nice-to-haves. In order to come up with sensible suggestions during this process, it is paramount for city planners to take a close look at the neighborhoods, the residents and what drives their behavior. They must break down traditional census-based demographics into actual consumer styles, to look beyond pure economical KPIs – because not all consumers in a certain demographic will be equally inclined towards alternative mobility solutions. For instance, locally based sharing offers, such as cargo e-bikes, can be a good way to replace car trips for grocery shopping or even larger scale errands, but will only be adopted if they fit to the local lifestyles.

Once consumers’ new needs are clear, cities must foster business development on the municipal level, especially for local production and retailers. An open call for public funding of the best ideas could be a promising and engaging way of doing this. When selecting the grantees, local citizens should certainly be part of the committee to decide which projects should come to life in their neighborhood.

Looking further ahead, many people are likely to spend their holidays at home this year, or within their own country. This means another important task for city planners is to make sure that tourist and leisure attractions in and around towns are conveniently accessible through biking, public transport or demand-responsive modes. Green spaces within cities will remain more important than ever before, and so should be invested in, to deliver the highest possible quality of experience and attraction.

What experts say:

Despite increased local loyalty, people will still be driven by price for many purchases. If it’s significantly cheaper to go on Amazon and buy from China rather than from a local business, they will – especially if we start feeling the pinch of an economic slowdown. The choice of shopping locally will therefore be positively impacted by long term measures, such as subsidies to support local shops, and education campaigns on the “real” cost of things etc.

– Melina Christina, MaaS Product Manager, RATP Dev, France

About our data partner: MOTIONTAG creates value from motion data by providing anonymized insights into travel behaviors. This allows our clients to evaluate the profitability of actions. For example, by knowing what incentives are effective in curbing mobility-related CO2 emissions, and steering policy-making with precise, real-time data.

Learn more about urban mobility