(Re-post from the Eye Tracking the User Experience Blog. Aga is currently writing Eye Tracking the User Experience, A Practical Guide, to be published by Rosenfeld Media in 2013.)

By now everyone has probably heard of webcam eye tracking. If you haven’t, it is exactly what it sounds like – detecting a person’s gaze location using a webcam instead of a “real” eye tracker with all the bells and whistles, including infrared illuminators and high sensitivity cameras.

Because webcam eye tracking doesn’t require any specialized equipment, participants don’t have to come to a lab. They are tested remotely, sitting in front of their computer at home, wearing Happy Bunny pajamas and trying to keep their fat cat from rolling onto the keyboard. The only requirements are: a webcam, Internet connection, and eyes to track.

Companies that provide webcam eye tracking services include GazeHawk and EyeTrackShop (YouEye has had a website for as long as I can remember but their webcam eye tracking doesn’t seem to be available yet). These companies recruit participants, administer the study, create visualizations, and report data by area-of-interest.

After reading about a few of their studies, including EyeTrackShop’s recent Facebook vs. Google+ hit, I decided to experience webcam eye tracking first-hand. I signed up to be a participant.

One day I was sitting in a comfy leather chair at a Starbucks with my laptop in my lap, working on chapter 10 of my book on eye tracking, when an “Earn up to $4” email came through to let me know I had a GazeHawk study waiting for me. Because any distraction is a welcome distraction when I’m writing (in case you’re wondering what’s taking me so long), I decided to take an educational break and follow the link.

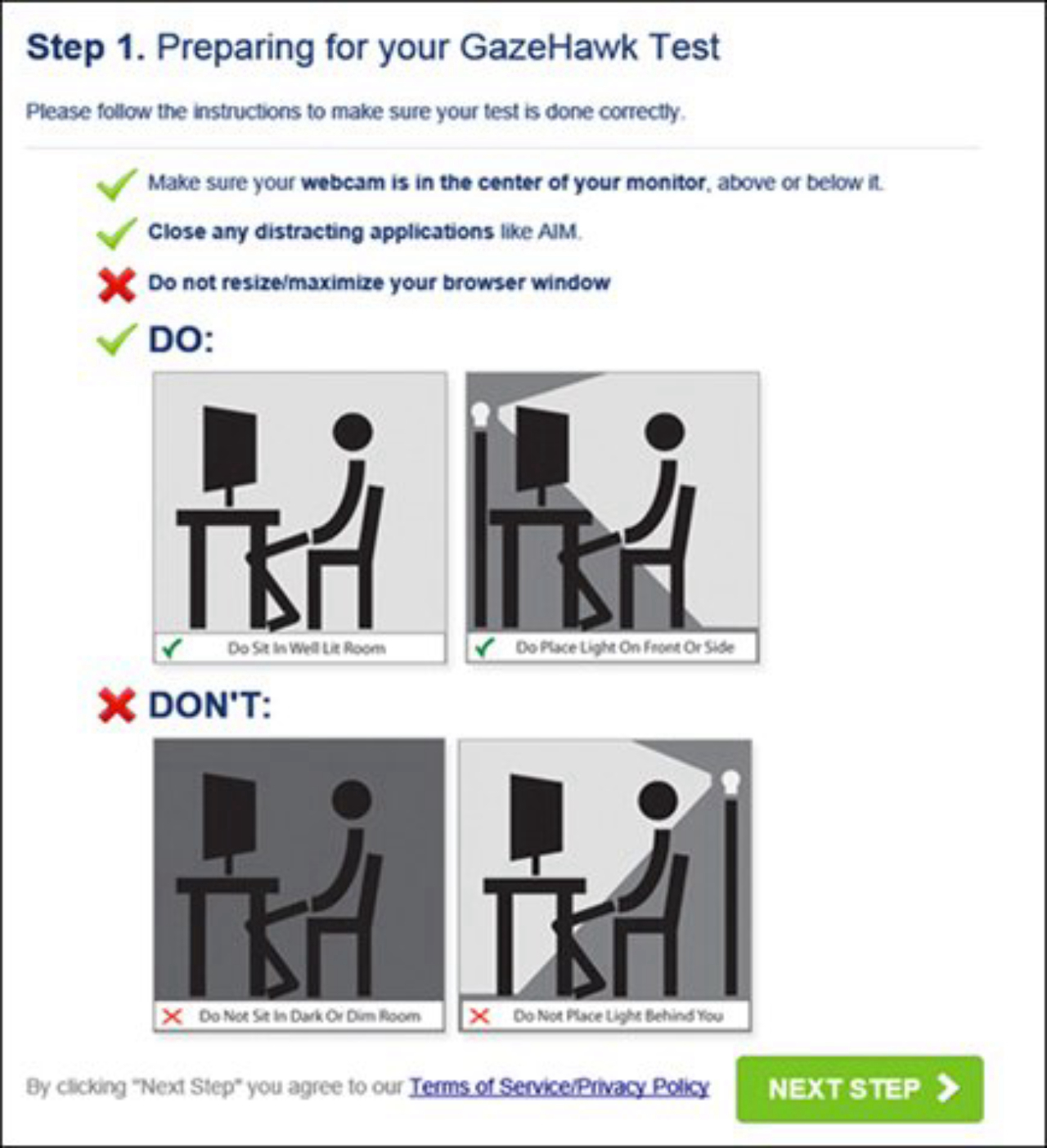

The first page informed me about how to prepare for the test.

(All screenshots courtesy of GazeHawk (thanks!).)

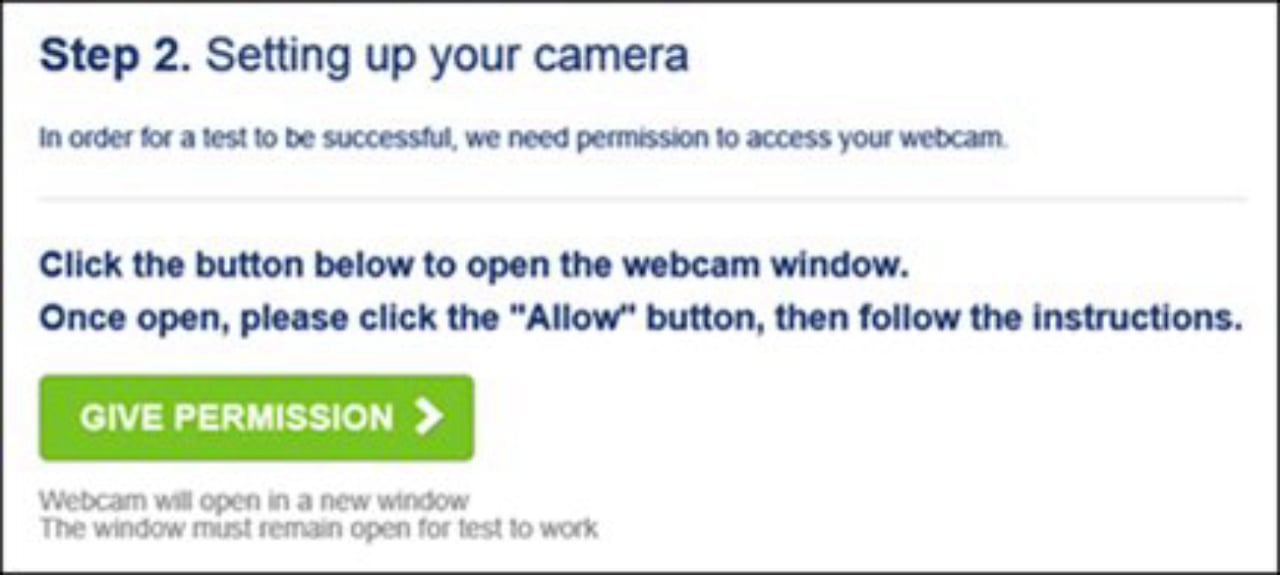

The lighting at Starbucks seemed to match the “DO” pictures, so I proceeded. I was then asked for access to my webcam, which I promptly granted, only to discover that even a webcam adds 10 pounds.

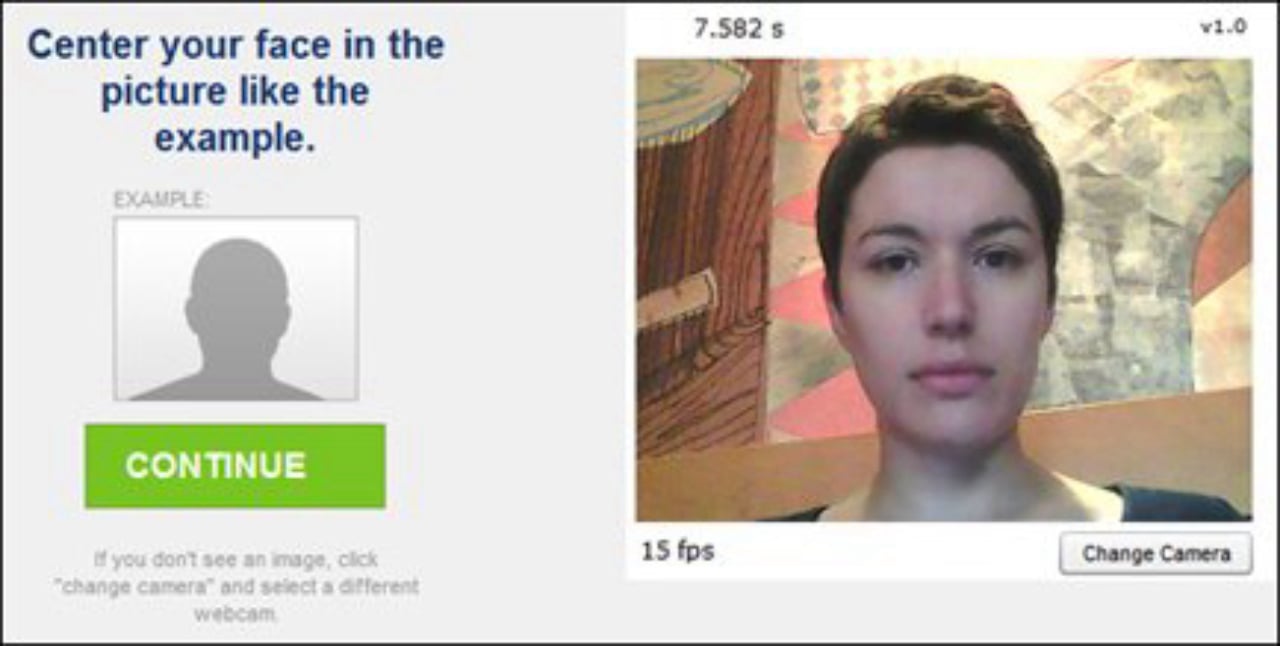

I centered my face in the window and was ready for calibration.

I followed the red dot as instructed.

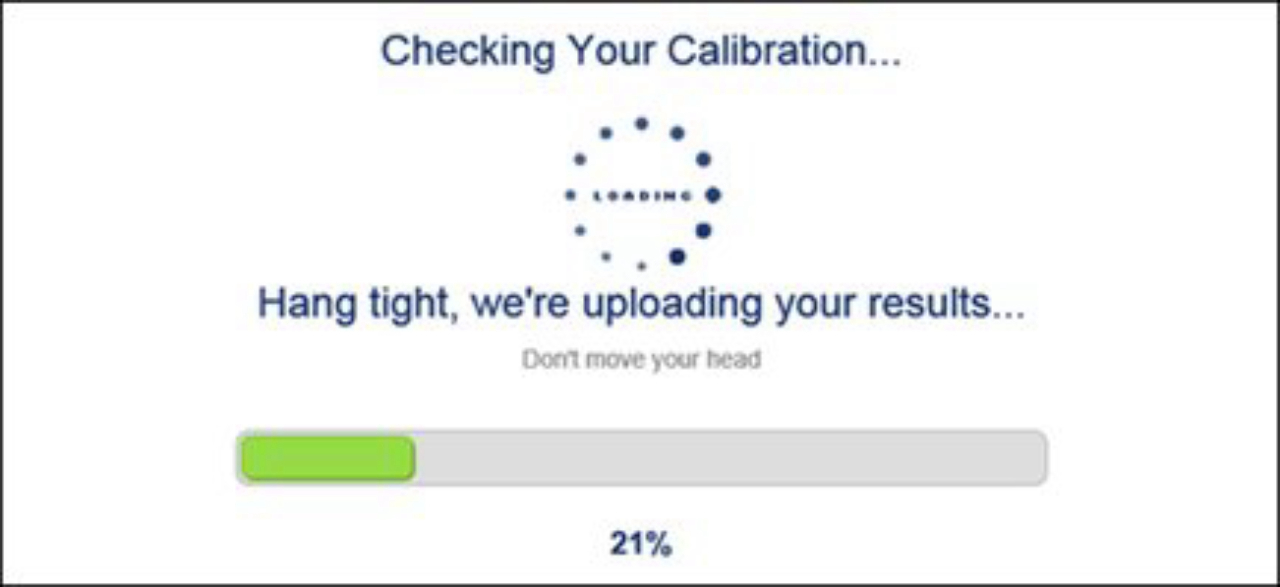

While my “results” were being uploaded (which seemed like a lifetime), I managed to check Twitter, finish my pumpkin bread, send a few text messages, and help a kid plug in his laptop into the outlet behind my chair. I then realized the instructions on the screen said not to move my head during the upload. Oops. Even though there was no mention about moving the webcam (or the whole laptop), I figured I shouldn’t have done that either. Good thing I didn’t get up to get a refill!

When the screen was finally ready for me to start testing, I was several minutes older and my calibration was probably already invalid, but since the interface didn’t request a do-over, I continued with the study.

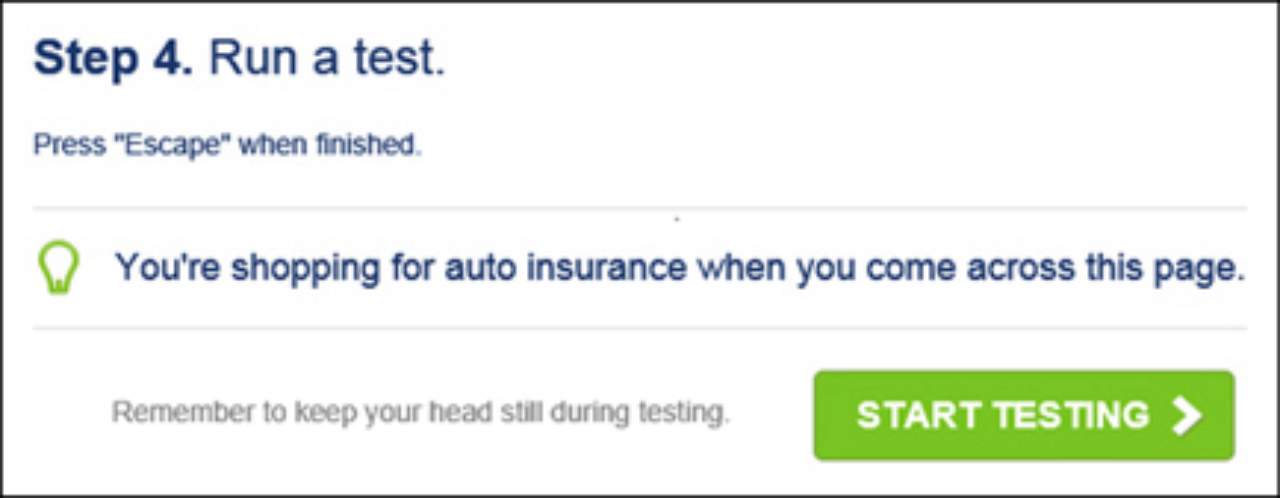

Step 4 of the process provided a scenario (auto insurance shopping) and instructed me to press Escape when I was done. I wasn’t quite sure with what I was supposed to be finished in order to press Escape but I clicked on “Start Testing” anyway. An insurance company homepage appeared.

A second or two later my Outlook displayed an email notification, and the compulsive email checker that I am, I opened the email. I also had to open it on my BlackBerry or the red light would have kept blinking for a while and I can’t stand that.

I came back to the insurance homepage and looked around for a while but nothing was clickable – the page appeared to be static. I then remembered the instructions I saw previously, and the Escape key saved the day.

Based on this experience, a few other studies I participated in, and my conversations with people involved with GazeHawk and EyeTrackShop, I made a list of what I believe are the main limitations of this new technology:

1. Webcam eye tracking has much lower accuracy than real eye trackers. While a typical remote eye tracker (e.g., Tobii T60) has accuracy of 0.5 degrees of visual angle, a webcam will produce accuracy of 2 – 5 degrees, provided that the participant is NOT MOVING. To give you an idea of what that means, five degrees correspond to 2.5 inches (6 cm) on a computer monitor (assuming viewing distance of 27 inches), so the actual gaze location could be anywhere within a radius of 2.5 inches from the gaze location recorded with a webcam. I don’t know about you but I wouldn’t be comfortable with that level of inaccuracy in my studies.

2. What decreases the accuracy of webcam eye tracking even further is when participants move their heads, and the longer the session, the more likely this will happen. Therefore, webcam eye tracking sessions have to be very short – typically less than 5 minutes, but ideally less than a minute. Studies conducted with real eye trackers, on the other hand, can last a lot longer with little impact on accuracy.

3. Currently, webcam eye tracking can handle only single static pages. All four studies I have participated in and a few I read about were one-page studies. Without allowing participants to click on anything and go to another page, the applicability of webcam eye tracking is limited. This constraint also lowers the external validity of the studies.

4. The rate at which the gaze location is sampled is much lower for webcams than real eye trackers. The typical frame rate of a remote (i.e., non-wearable) eye tracker is between 60 and 500 Hz (i.e., images per second). The webcam frame rate is somewhere between 5 and 30 Hz. The low frame rate makes analyzing fixations and saccades impossible. The analysis is limited to looking at rough gaze points.

5. Due to imperfect lighting conditions, poor webcams, on-screen distractions, participants’ head movement, and overall lower tracking robustness, out of every 10 people who participate in a study, only 3 – 7 will provide sufficiently useful data. While this may not be a problem in and of itself because of very low oversampling costs, what makes me uncomfortable is not knowing how the determination to exclude data from the analysis is made. Data cleansing is important in any study but it is absolutely critical in webcam eye tracking. Exclusion criteria should be made explicit for webcam eye tracking to gain trust among researchers.

Regardless of its limitations, the contribution of webcam eye tracking to research is undeniable. Using webcams made it possible to conduct remote eye tracking studies and enjoy the benefits of remote testing, such as low cost, fast data collection, and global reach.

While webcam eye tracking is not a substitute for in-person research that uses real eye trackers, it is a cheap option if you’re looking for a quick and dirty indication of the distribution of attention on a single page (e.g., your homepage or an ad). As the technology and data collection processes employed by these services continue to improve, the applicability of webcam eye tracking will expand. Will it ever replace eye tracking as we know it? Doubtful, but I will keep an eye on it anyway.

![Understanding your audience: The power of segmentation in retail [podcast]](https://nielseniq.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/07/Podcast-Understanding_your_audience-The_power_of_segmentation_in_retail-mirrored.jpg?w=1024)