Navigating uncertainty with resilience

Today’s business leaders are facing a uniquely challenging moment: Shifting policies, fluctuating consumer sentiment, and economic uncertainty have created an unpredictable environment where day-to-day decision-making—let alone planning for the future—feels overwhelming.

In moments like these, most economic outlooks offer broad trends or surface-level forecasts. This one is different.

We’re delighted to once again collaborate with Yale economists Martha Gimbel and Ernie Tedeschi to bring you this business resiliency playbook. Taking a deep dive into 50 years of historical US data, they reviewed consumer behavior across major economic shocks—from recessions and stagflation to geopolitical crisis. Their analysis reveals not only how consumers respond in each scenario, but also the key signals that indicate shifts are coming.

Making this playbook actionable is our business resiliency framework—a detailed guide that outlines how to interpret these signals, along with specific steps retailers and manufacturers can take to respond to them with agility and confidence. We hope you’ll use it as a strategic compass to guide your planning and position your business for resilience and growth in the months ahead.

Vice President, Global Thought Leadership, NIQ

Courtenay Verret is Vice President, Global Thought Leadership at NIQ, where she connects data-driven insights with compelling narratives that position the company at the forefront of consumer intelligence. Her work spans critical topics such as AI, innovation, and brand marketing, helping shape strategic conversations. Courtenay plays a key role in amplifying NIQ’s brand authority by fostering influential partnerships, driving executive engagement, and delivering insights that resonate across industries and markets.

About the authors

Economist

Martha Gimbel is the Executive Director of The Budget Lab at Yale. She has worked as an advisor and an economist in senior roles across government, the private sector, and philanthropy, including the White House Council of Economic Advisers, the Department of Labor, the Joint Economic Committee on Capitol Hill, Schmidt Futures, and Indeed.com. She is an expert in a range of economic data, including the labor market, consumer spending, inflation, and economic growth, and in how economic and policy dynamics intersect.

Economist

Ernie Tedeschi is the Director of Economics at The Budget Lab at Yale and a Visiting Fellow at the Psaros Center for Financial Markets and Policy at Georgetown University. He is also a regular Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Until March 2024, he was the Chief Economist at the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). Prior to CEA, Ernie was Managing Director and Head of Fiscal Analysis at Evercore ISI. He has also been an economist at the US Department of the Treasury and a contributor to the New York Times Upshot column.

What drives consumer behavior in periods of uncertainty? Get a preview of what you’ll find in The Business Resiliency Playbook—and then keep reading!

Want to read later?

Planning for business resilience? Or decision-making in the dark?

Where is the economy heading?

And how will consumers respond?

These questions are undoubtedly top of mind for manufacturers and retailers as they face a global economic landscape marked by an extraordinary degree of uncertainty. But in our quest to forecast what’s coming, are we overcomplicating what really matters for building business resilience?

From shifting trade policies and geopolitical tensions to volatile financial markets and evolving consumer behaviors, today’s environment is more unpredictable now than at any point since the pandemic five years ago. This uncertainty is not an abstraction—it’s a daily reality, shaping the decisions of businesses, policymakers, and consumers alike.

For business leaders, this unpredictability presents a challenge: Decisions about pricing, hiring, supply chain investments, brand positioning, and innovation pipelines must be made in the face of incomplete information and rapidly changing conditions. Traditional models and former precedents may no longer provide reliable guidance, making it difficult to chart a clear path forward. Yet, choosing not to act—delaying key decisions or defaulting to the status quo—is also itself a decision, one that can leave organizations exposed to risks and missed opportunities.

In a 2022 report, McKinsey found that the actions a company takes before any sort of economic shock—for example, what it does to prepare or where it invests—could account for as much as half of the gap in shareholder returns between leaders and those who lag behind.

In this context, business resiliency planning isn’t just advisable—it’s essential. The manufacturers and retailers best positioned to navigate uncertainty are those that have proactively developed strategies to withstand shocks and adapt to new realities. But before crafting a resilient plan, it’s crucial to first understand the potential scenarios that could unfold over the next couple years. This requires a rigorous assessment of both the risks of the current environment and a thoughtful exploration of how similar risks played out in the past.

For this report, we’ve designed an analysis to give business leaders the insights they need to anticipate and prepare for a range of possible futures. By mapping out distinct scenarios for consumer spending, we aim to provide a framework that enables agile decision-making and strategic foresight. Our goal isn’t to predict the future, but to help organizations develop robust plans that can adapt as conditions evolve.

To do this, we draw on experiences of the past to help calibrate what the next couple years might hold. Historical episodes—the stagflation of the 1970s, the significant recession of the early 1980s, the mild recession of 1990, the soft landing of the mid-1990s, and the oil/geopolitical shock of 2022—offer invaluable lessons in how consumers respond to economic disruptions and uncertainty. During such periods, consumer priorities often shift rapidly, with spending on essentials taking precedence over discretionary purchases, and brand loyalty being redefined by perceived value and trust.

Importantly, our analysis suggests three key findings:

1

First, across each of the historical episodes we reviewed, consumer behavior followed similar patterns, regardless of the stimulus. Moving forward, it’s crucial that business leaders not put too much weight on which stimulus consumers will react to. Consumers don’t care why they’re stressed—they just know that they are. And they tend to respond accordingly.

2

Second, as predicted, in each of the economic scenarios we reviewed, consumers pulled back on “nice-to-haves” and gravitated toward value-seeking behavior, to greater or lesser extents, depending on the size of the shock. Rather than anticipating an infinite number of scenarios, business leaders should instead stay attuned to the key data signals flagged here that could indicate a behavioral shift is coming.

3

Critically, at the time of this analysis (summer 2025), the NIQ data we reviewed indicates that consumers aren’t demonstrating widespread signs of stressed behavior, despite recent fluctuations in sentiment. This could change at any time, given dynamic conditions on the ground, but it reinforces the idea that consumer sentiment is only one data point to act on. Business leaders must stay vigilant—and balance what consumers say with actual shifts in what they do.

“Our goal isn’t to predict the future, but to help organizations develop robust plans that can adapt as conditions evolve.”

Past is prologue: Five historical scenarios that could mirror future outlook

The outlook for the US economy over the next two to three years is unusually uncertain, with several plausible scenarios—each carrying different implications for growth, inflation, and consumer spending.

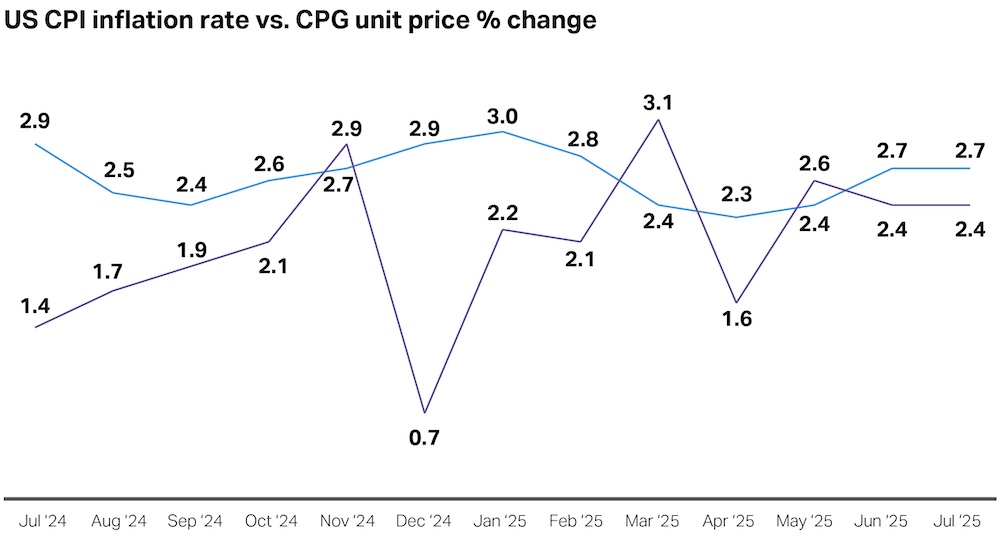

Despite volatility month to month, real consumer spending is still up nearly 1% since last October, and real durable goods spending is up nearly 2%. A largely stable labor market has been supporting the consumer (although recent data suggests signs of weakening), while wages and income growth have grown faster than inflation, providing some support to consumer purchasing power despite persistent price pressures. Inflation is still slightly elevated but has come down from the unusually high levels (e.g., 7–9%) of 2022.

Consumer sentiment and broader economic indicators are mixed, however. The Consumer Confidence Index and University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers have both shown a rebound since their lows earlier this year; however, consumer attitudes are still down from late 2024. Meanwhile, preliminary results from NIQ’s annual Consumer Outlook survey indicate overall increased levels of optimism since a year ago; however, concerns about the potential for rising food prices, economic downturn, and geopolitical conflict remain top of mind for most—illustrating just how challenging it is to keep up with consumer mindsets during this time.

Economic growth has also been mixed: Real GDP growth was negative in Q1 2025 but beat expectations, at 3%, in Q2. Even with this bounce back, average growth over these first two quarters was still only 1.2%, down from 2.5% in 2024. There also could be upward inflation pressure and labor supply contraction over the next year, depending on evolving US policies (e.g., trade, immigration, Federal Reserve prime rate, reconciliation tax package).

Drawing on both current data and historical parallels, we can outline five principal scenarios that could impact the US economy and challenge business resilience over the next few years:

- Stagflation

- Mild recession

- Deep recession

- Soft landing

- Geopolitical shock

Note that these are not intended to cover all possibilities, nor are they mutually exclusive. A recession may be “stagflationary,” for example, while geopolitical shocks may underpin all of them. The direction the economy ultimately takes will depend on the interplay of monetary and fiscal policy, the trajectory of inflation, the evolution of global trade and geopolitical risks, and the resilience of consumer demand.

Stagflation (1970s)

“Stagflation” is characterized by slow growth, high unemployment, and persistent inflation. This scenario echoes the 1970s, when oil shocks and policy missteps produced a toxic mix of high prices and stagnant output. During that era, consumers sharply curtailed discretionary spending, trading down in categories like Apparel and Durable Goods, while prioritizing essentials such as Food, Energy, and Housing.

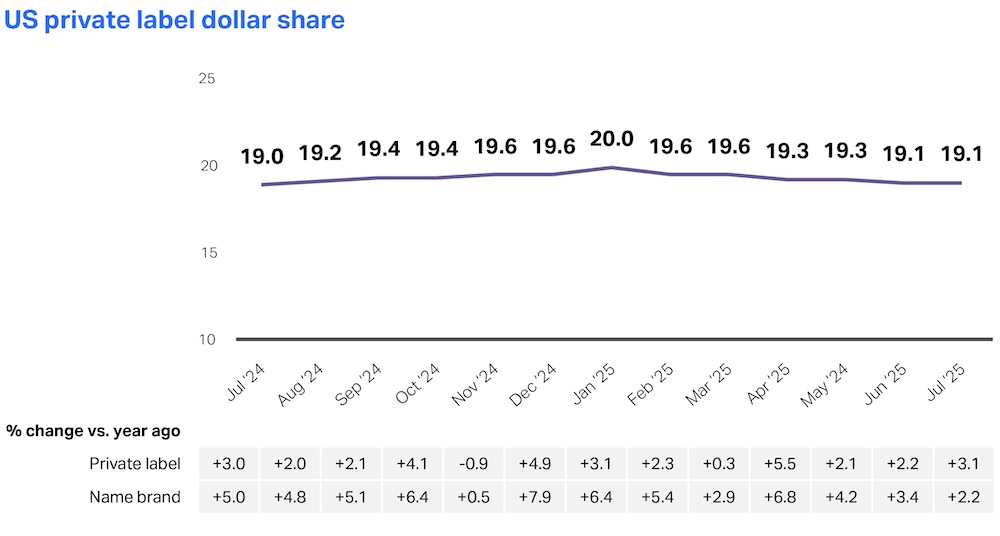

Like in the 1970s, brands with strong value propositions, including private label alternatives, might gain share, while loyalty could erode in the face of rising prices.

Mild recession (1990–1991)

A recession is a sustained contraction in economic activity. A “mild” recession would be reminiscent of 1990–1991, when growth slowed sharply but systemic financial distress was avoided. Typically, the unemployment rate would rise. In the wake of 1990, it ultimately rose about 2 percentage points, but in principle a smaller rise might still be consistent with a recession call. In the end, real goods spending declined by 4% between July 1990 and January 1991.

In this scenario, like in the early 1990s, consumer spending would likely decline—especially for big-ticket categories like Autos, Home Furnishings, and Travel. Essentials would be less affected, but even here, consumers would likely trade down or delay purchases.

Deep recession (1980–1981)

A deeper recession, akin to the early 1980s, could result in a significant unemployment spike and a more pronounced slump in discretionary and durable goods spending. The unemployment rate rose 5 percentage points after 1980, and real goods spending dipped 6% lower, not recovering to January 1980 levels until early 1983.

Historically, these periods see sharp drops in home construction, vehicle sales, and luxury goods, while discount and value retailers outperform.

Soft landing (mid-1990s)

A “soft landing” is the most optimistic scenario we’re examining, in which the US Federal Reserve successfully brings inflation down to its 2% target without triggering a recession. In this case, growth could slow but remain solidly positive (around 1.5–2% annually), the unemployment rate would edge up only slightly (stay below 5%), and, as mentioned, inflation would gradually return to target levels. The mid-1990s offer a historical parallel: The Fed preemptively raised rates to cool inflation, but the economy continued to expand, and consumer spending remained resilient, albeit with some shifts toward value and essentials.

In this environment, discretionary spending would likely stabilize, and categories tied to home improvement, travel, and experiences could see renewed growth as consumer confidence recovers.

Geopolitical shock (2022)

Geopolitical events—such as escalated conflict in Eastern Europe or instability in the Middle East—could also deliver sudden shocks to the economy. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example, caused energy and commodity prices to spike, eroding consumer purchasing power and triggering market volatility, but ultimately having little to no impact on the labor market. The 1973 energy shock had much more serious consequences.

In such scenarios, inflation could re-accelerate even as growth slows, leading to a “stagflation-lite” environment. Consumers would likely respond by further prioritizing necessities, trading down in food and household goods, and deferring discretionary purchases. Supply chain resilience and pricing flexibility would be critical for businesses navigating such shocks.

Key takeaways:

- Economic signals are currently mixed: While spending is up, growth has slowed from last year and consumer sentiment is in flux.

- Multiple economic paths are plausible—each with distinct business implications.

- The direction the economy ultimately takes will depend on the interplay of monetary and fiscal policy, the trajectory of inflation, the evolution of global trade and geopolitical risks, and the resilience of consumer demand.

Different shocks, familiar patterns: Decoding consumer behavior under pressure

In a soft landing, we would expect current consumer trends to continue and not see a huge break from present-day behaviors. But how does consumer spending for different goods respond under the other macroeconomic scenarios?

To assess this question, we share two layers of analysis:

- The first looks back historically at periods that align with the macroeconomic scenarios laid out above and calculates how real consumer spending (inflation-adjusted Personal Consumption Expenditures—or PCE—from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis) changed over the subsequent two years.1 We show the results for four of these periods relative to the soft-landing period that began in January. PCE categories cover all monthly consumer spending, including services, but lack the detail to answer important questions—for example, the ability to distinguish within categories among different brands.

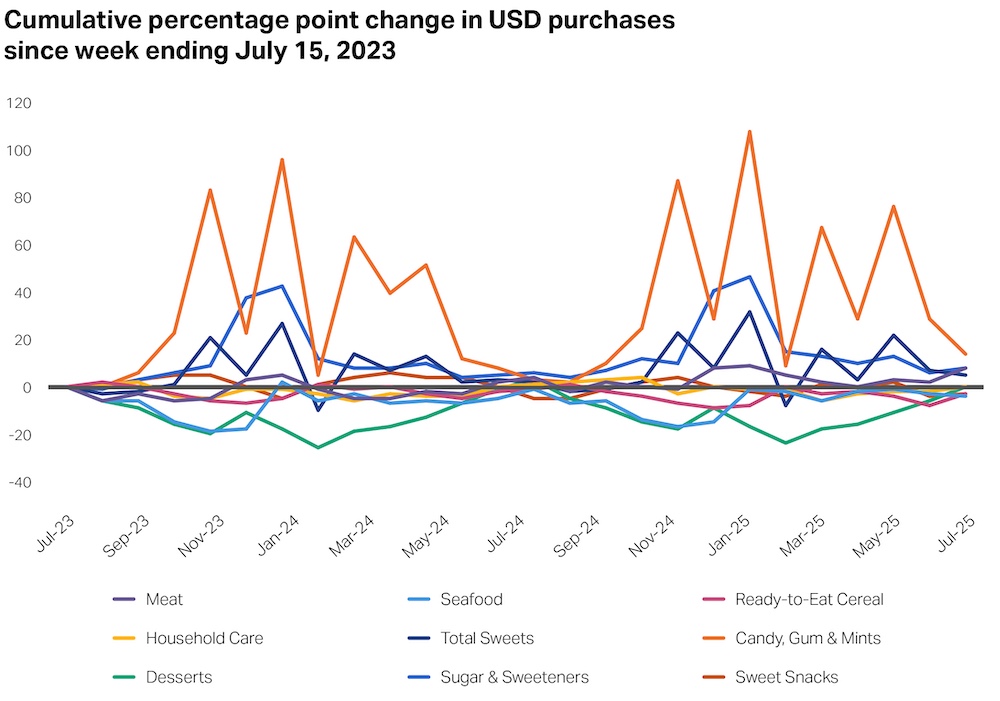

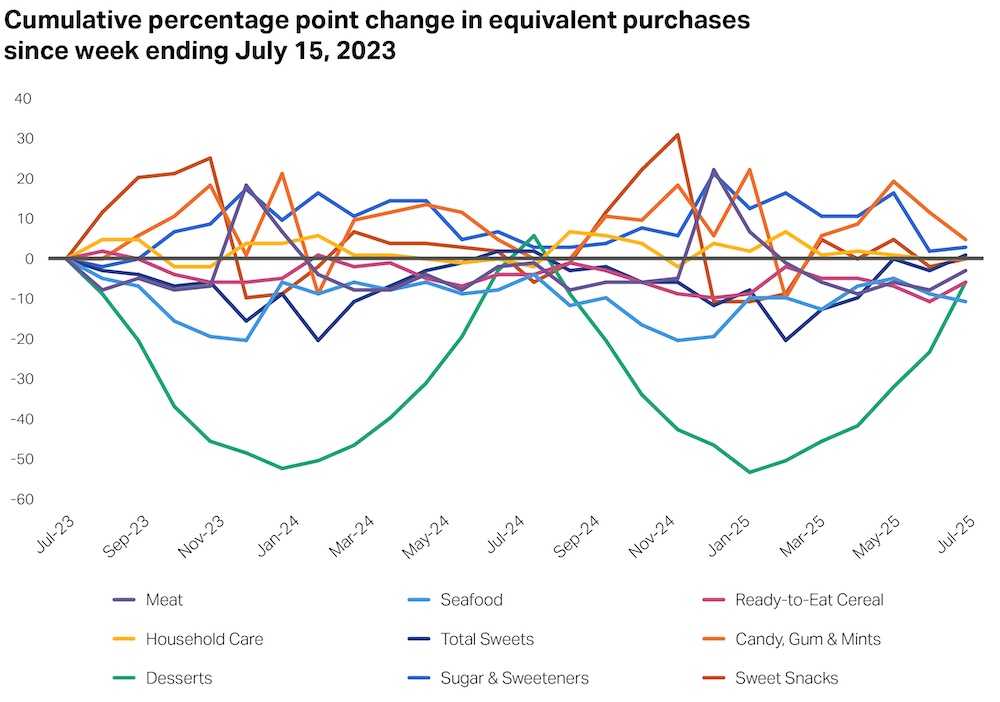

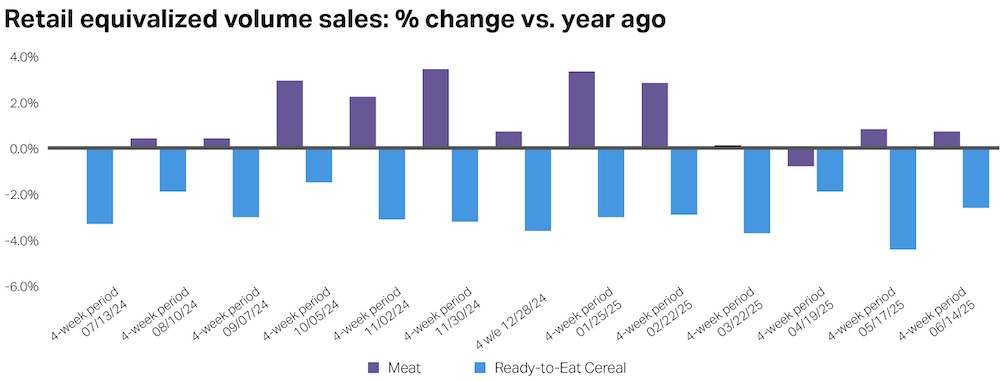

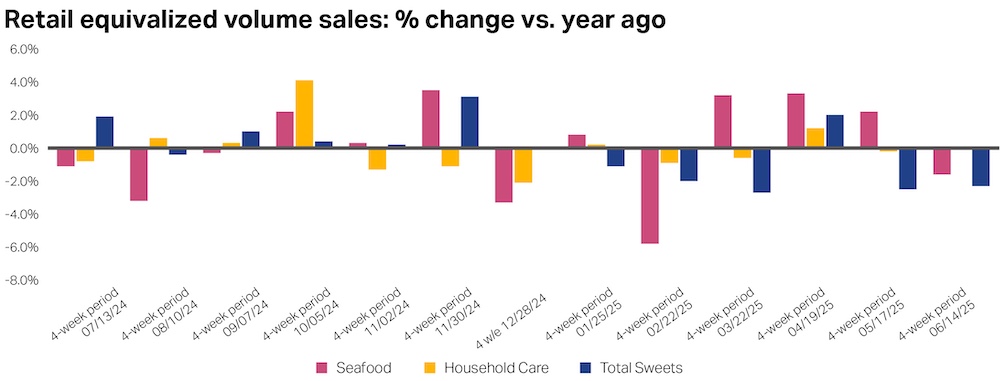

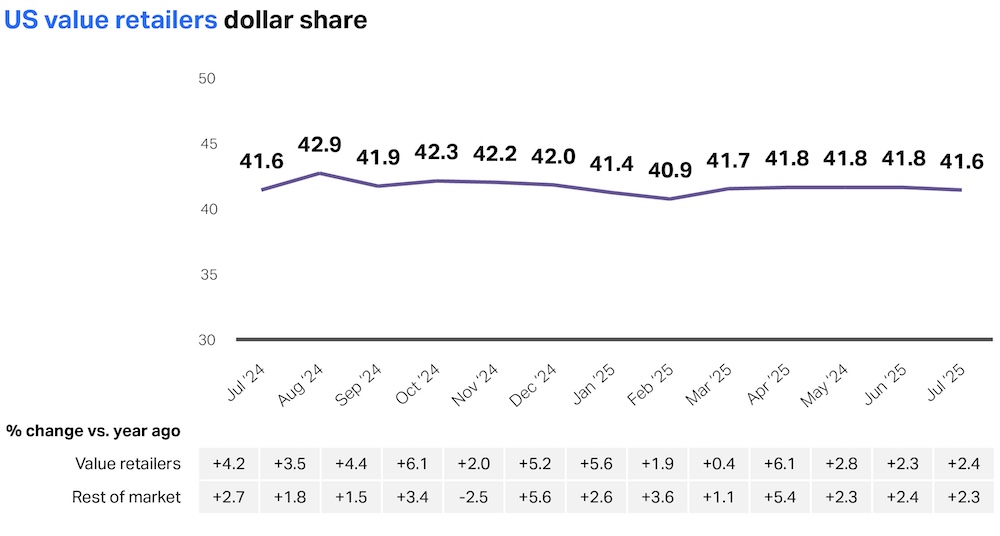

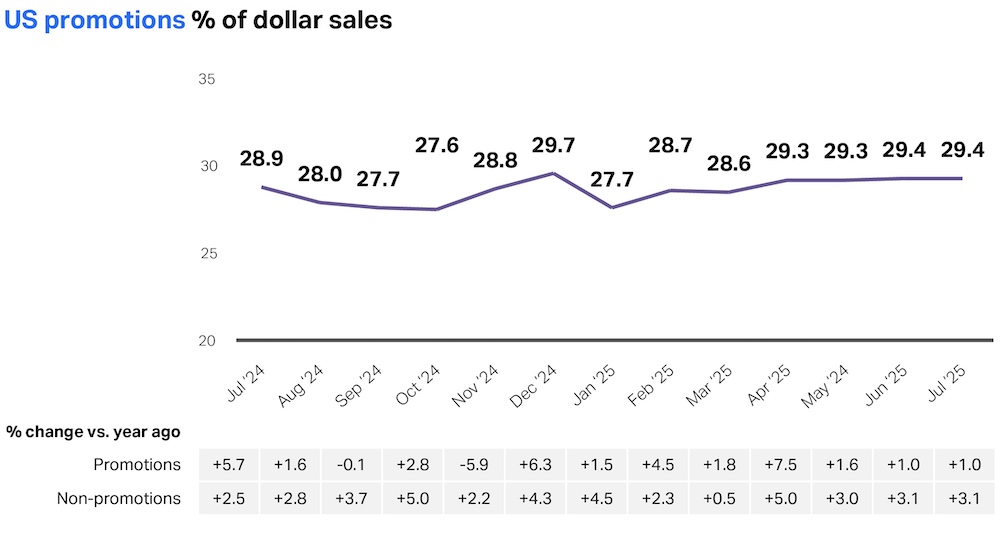

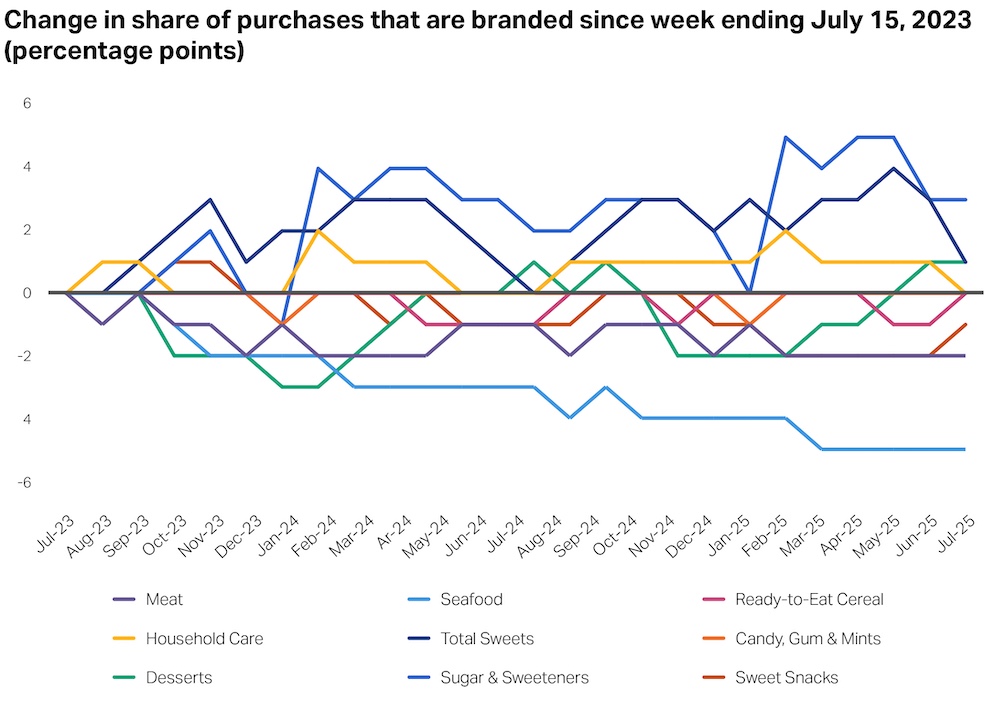

- In the second analysis, we use NIQ data to dig more deeply into some of the most historically sensitive product categories, which allows for more differentiation between products and high-frequency detail.

1 Full results of the analysis are in the chart labeled “Full historical real PCE consumer goods analysis.” In summary, the analysis calculates the percent “gap” of monthly real consumer spending per capita for each of nearly 200 PCE categories against trend. “Trend” here is calculated as the Hodrick–Prescott (HP)–filtered trend of log real spending per capita for each category with a band-pass window of 20 years (equivalent to an HP smoothing parameter of roughly two million). The calculation of trend allows the analysis to account for long-run consumer preference changes. The change in the gap shown in the chart for each historical period is the average percentage point gap over the second year out (13–24 months from the beginning of each period) minus the average gap over the 12 months ending with the period start (the month of the period start itself plus the 11 preceding months).

The outcome of our first analysis suggests a perhaps surprising result: To prep for consumer behavior under one outcome is to be well-prepared for the other outcomes as well. In general, across all economic shocks we evaluated, consumer behavior followed similar patterns.

During times of economic stress—regardless of its classification or cause—consumers tend to pull back on bicycles, cars, sugar and sweets, and photographic equipment, among other goods. Few goods are left unaffected—although some are affected less (e.g., tobacco). Unsurprisingly, “nice-to-haves” are more affected than “need-to-haves” when consumers have to pull back—the exception being a small treat or affordable luxury that can substitute for bigger savings (e.g., an increase in spending on meat in the face of a recession likely reflects that consumers are no longer going to restaurants and are instead buying more to cook at home).

Interestingly, as the continuation of our chart below shows, some categories actually saw increases in spending—including watches and “pleasure aircraft.” This may suggest that luxury spending can hold up relatively well during times of change, as more well-off consumers remain insulated from economic swings.

Although the stress response across scenarios is similar, the scale and speed of that response is likely proportional to the magnitude of the shock. In other words: The more severe the disruption, the faster and more pronounced the behavioral shifts will likely be. A major recession may trigger swift and widespread pullbacks, whereas a mild downturn or stagflation might result in more gradual or limited adjustments. Similarly, some geopolitical shocks could rival the economic impact of traditional recessions, depending on their scope and consumer visibility. Understanding this scaling effect is critical for anticipating the depth and duration of demand shifts across categories.

Especially in periods of change, building business resiliency means being prepared and staying attuned to the data to see trends as they emerge. Unfortunately, this can pose a challenge for several reasons:

1

Leaders must navigate not only where to look, but also what to look for. They must determine which data sources are the most effective for their business, as well as the most relevant shifts in consumer behavior they should be monitoring in uncertain times.

2

Leaders must understand not only the overall spending picture, but also how consumers are adjusting their behavior in the shopping aisle and across channels in real time. Are they trading down, switching to private label or seeking deals, pantry loading, or pursuing other money-saving strategies?

3

Leaders must anticipate change. Due to the publishing lag time and backward-looking nature of government data, it can be difficult to capture trends as they emerge.

Regardless of category, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) data makes an ideal use case for pulse checking the state of the consumer. Given its high turnover rate, variety of purchasing channels, and opportunities to trade up or down, we can see even slight behavioral shifts that, in combination with our historical analysis and consumer sentiment data, might signal larger emerging trends. By regularly monitoring overall market and category data—especially those that are historically sensitive during economic shocks—businesses can anticipate needed price adjustments and promotions, right-size their product portfolios, and adjust marketing strategies and budgets.